First Italian, then Thai, and now finally in English, The King of Bangkok is an “enthographic” novel from Claudio Sopranzetti, Sara Fabbri, and Chiara Natalucci mapping the complex personal politics and trauma of Thailand’s recent political history. BK Magazine speaks with Claudio Sopranzetti about his research journey and what this graphic novel can tell us about the city’s present.

Can you tell our readers a little about the story The King of Bangkok hopes to tell?

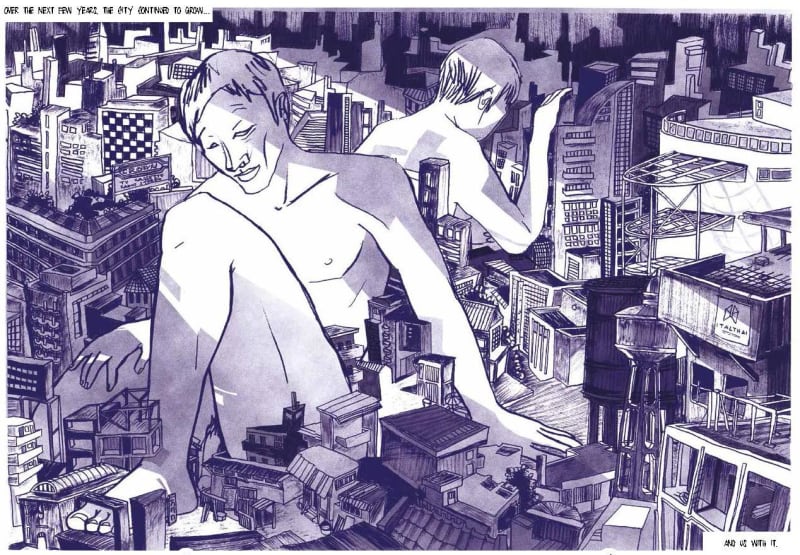

The King of Bangkok came out of a real story of a few characters I met while I was studying anthropology—and in particular started with one character who was the driving force of the story. This guy was a motorcycle taxi driver in the early 2000s and got shot during the Red Shirt protests and was blinded. It’s a really fascinating and interesting story. It all started in some small ways from that but I didn’t just want to put one person on the spot for the consequences of Thailand’s political movements. I basically blended three or four characters I interviewed into one character. The story is a very ordinary story in Bangkok, frankly—the story of a guy who is from the northeast who slowly becomes more accustomed to the city. It’s the people we see in the streets of Bangkok: the workers, taxi drivers, street vendors. I wanted to tell the story of a whole portion of Thai society. In some ways it’s the story of a city through an ordinary man.

Why did you choose a graphic novel to tell this type of a story?

The answer is in the three people who are the authorial team of this book. I think what’s important to mention is it’s not the classic one writer, one person doing the editing, one person doing research. It was really a collective project. Every word and every image was discussed. For me, it was frustrating that my academic life involved writing books that took a lot of work and then no one read. It was the frustration of reaching no one and screaming in an empty room. I had a conversation with Chiara (Chiara Natalucci) and she was working with publishing in London and she thought we should go in that direction. From there we reached out to artists to find one we liked. When we translated the book into Thai, it did really well, sold a lot of copies, and won prizes. But initially the response from many of the big publishers was that comics are for young people, children. And they said there was no market in Thailand for a heavy political comic. It was really nice to see that this was not the case. There was this attempt on one side to have a bigger audience, on the other to experiment with a new type of narrative. The format is more common in the US, Europe, or Japan, but in Thailand it’s in the process of emerging, so we are really happy to be part of that process.

It’s 2022 now. We’ve had a rough few years. What lessons can people today take from the story of The King of Bangkok?

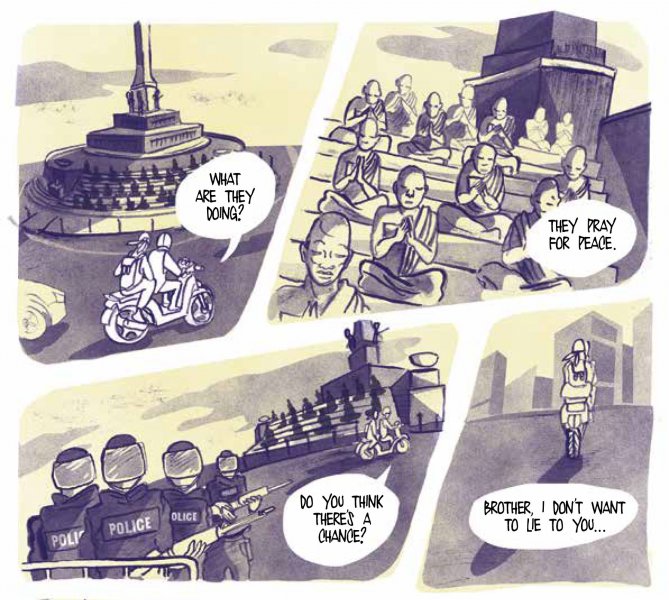

I think what a graphic novel allows is multiple levels of interpretation and analysis. It’s kind of built into the format. In terms of messages, I think thematically there are layers. You know, a lot of our readers in Thailand are middle class and this is not necessarily a story they are familiar with. This is not the story of politics that they experience. So the first step and the first message is to show that different parts of society were going through a political transformation—a change in the way they understand their relationship with the state, with the country. One thing we did was show the way news comes into contact with the people. In the beginning they come to a radio and they kind of distractedly listen to it, then TV where they pay attention, and then they become part of the national news.

Another thing, especially in relation to the contemporary protests, is a memory of faces of political protests. What’s interesting is what the government has been doing over the course of the last 10 years and what military governments always do: erase memory. Memory itself in Thailand is a very contested territory. It’s a territory where erasure is a big force. So part of what we want to do is say, okay, what if we create a story that is readable and combats this process of erasure.

So, what’s next for you? What’s the next big project?

Oh, well, that’s quite complicated. You know, because of Covid I haven’t been back to Thailand in like two years. That’s my second home so it’s a very strange sensation for me. My own work now is a lot more historical because I can do it from far away. I think my work is very responsive, so it depends a bit on what happens next in the political movements there.