Food brings us together, but not everyone gets a seat at the table in our food system.

Farmers play a key role in the lives of all working-class people: you can survive without many material goods, but you can’t live without food. Nevertheless, in Thailand farmers are among the country’s most marginalized and underpaid—

according to the United Nations, the agriculture sector in Thailand “generates the lowest value added per worker.” For consumers, they are often out-of-sight, out-of-mind for consumers. So is their plight.

“Without proper education, [farmers] end up selling to large corporations at a steal of a price, leaving no room for negotiations, which then gives full rein to these conglomerates to sell [their products] at high prices to the consumer,” says Dharath Hoonchamlong, a co-founder of nomadic bar Wasteland and food scholar. “The farmers end up getting the scraps.”

When they rely on conglomerates, farmers limit their potential earnings and bargaining power. At the same time, economic pressures—investing in equipment to boost production or meet the high bar of going organic—force them to make hard decisions, like relying on pesticides or selling products at low prices to ensure they receive any profits at all.

But some entrepreneurs are trying to change the forecast for Thai farmers. In the process, they hope to build a more sustainable food system that links you to the food you eat and the people who grow it.

No middleman, no problem

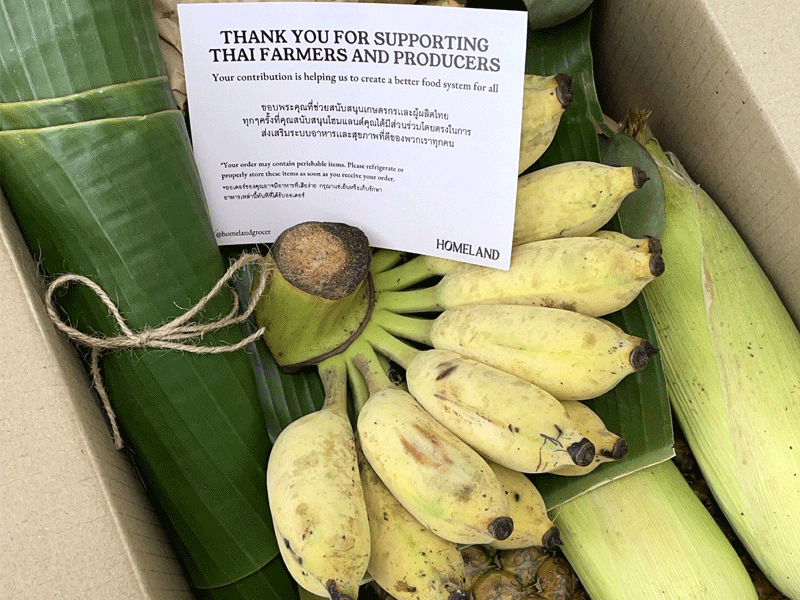

Image Courtesy of Homeland Grocer.

What does social media have to do with your food? For Pattaraporn “Nat” Salirathavibhaga and Natnicha “Tess” Burapachaisri, quite a bit.

With their newly launched social platform, Homeland Grocer, the two are employing the power of storytelling on social media to build a healthier, more equitable, more resilient food system, “where we [have] pride and respect for the people who make and grow our food,” says Tess. Oh, and deliver great, fresh food to you, too.

Image Courtesy of Homeland Grocer.

Homeland Grocer sources from organic, small-scale, and family farmers and producers from places like Chiang Rai, Amnat Charoen, and Nakhon Pathom. They deliver these groceries directly to consumers in eco-friendly packaging with personalized notes about their mission. But they reiterate: they are not middlemen—they are partners who let farmers set their own prices.

Online, they work to demystify supply chain issues and put a face behind the food consumers buy. Homeland Grocer’s Instagram account is peppered with educational posts, highlighting not only locally grown produce, but also various ways on how to build a better food system.

Offline, fair trade is a key component of their work. They say it boosts farmers’ morale, leading them to work ethically and be more transparent. They also work in conjunction with the Thailand Organic Consumer Association (TOCA), who have built a transparent relationship with organic farmers, and continue to support capacity and skill development for Thai farmers and producers.

Image Courtesy of Homeland Grocer.

“When you buy from us, you directly contribute to… sustainable rural development that improves the livelihood of our partners, their families, and their communities,” says Tess.

Know where your food comes from

Image Courtesy of Happy Grocers.

Last year, Moh Suthasiny and Pearl Pattamaphon noticed the many ways the pandemic was disrupting Thailand’s food system, in particular the abundant food waste. They decided to act.

Their startup, Happy Grocers, is an online grocery store and mobile produce truck that delivers to homes and condos throughout the city. In other words, it brings the good stuff to you.

“Farmers were complaining that they couldn’t sell their products and our consumer friends were also finding it difficult to find certified organic produce,” Moh, who like Pearl has a background in agriculture, tells us.

“We already had the connections from our past work, so we decided to make a Facebook page, offering produce from our farmer friends. People responded well and we haven’t stopped since.”

Image Courtesy of Happy Grocers.

Moh and Pearl set out with simple but clear goals: getting good food into consumer hands while making things transparent and working only with certified organic suppliers.

A big part of their business revolves around “ugly” produce—the kind that supermarkets don’t like to stock, as consumers gravitate toward flaw-free fruits and veggies. They put it plain and simple on their website: “Over 60% of our products are those that don’t make it to conventional supermarket shelves because they don’t reach the beauty standard.”

Image Courtesy of Happy Grocers.

By selling these vegetables, they say that farmers are able to harvest more frequently, which then produces more revenue and reduces food waste by more than 40 percent.

In addition, the company schedules farm trips, cooking classes, and virtual workshops to boost consumer understanding of how their food is produced, and who is behind it.

Putting local beef on the menu

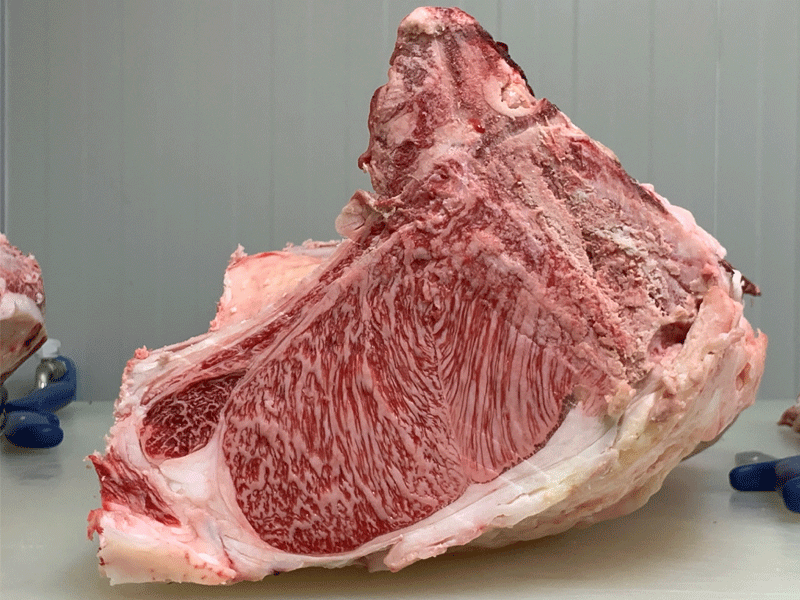

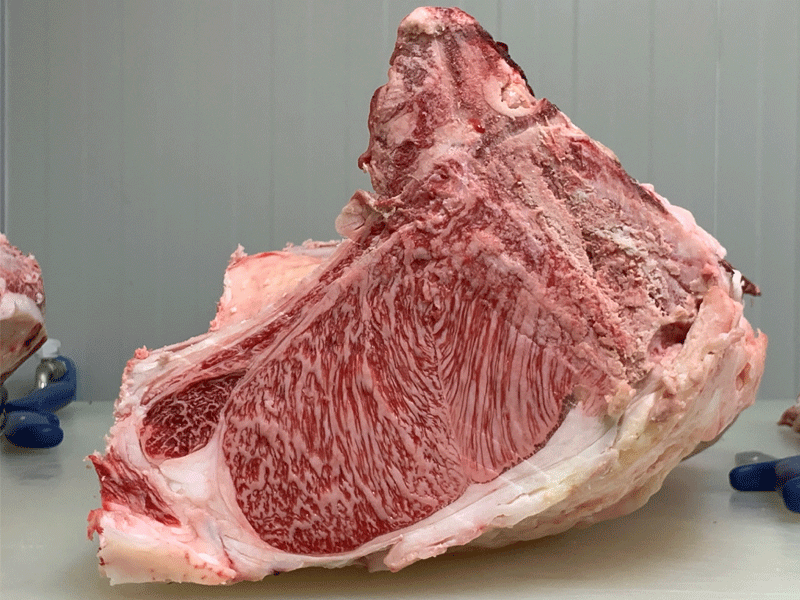

Image Courtesy of Groco.

While Happy Grocers is making ugly fruit more attractive, another company is trying to fix our relationship with meat.

Groco aims to help Thai cattle farmers raise livestock and sell meat in a sustainable manner. The first step in that process sounds a bit like psychiatry. Groco helps “farmers connect with the character of their produce or cattle and encourages them to see more value in it,” says Pitipong Matitanaviroom, who co-founded Groco with business partner Win Luanchaison.

A shift in attitude toward Thai meat is already underway, though. Over the past decade, restaurants have frequently turned to local suppliers for beef as the quality has increased, especially beef from farms in the Northeast. Now, you’ll find Thai beef proudly on the menu at restaurants like 100 Mahaseth, Taan, Appia, Samuay & Sons, and more.

Image Courtesy of Groco.

“Covid has changed the mindset of people when it comes to food, and not only chefs. Consumers are more and more curious about local beef,” explains Win. “That is why we work with [a variety of] farmers, such as Farm Arunsupa, because each source offers distinct characteristics and tastes, according to factors such as soil and altitude.”

But cattle farmers still face many problems with logistics and marketing.

Often their knowledge of the food system doesn’t go beyond the butchering process, and so they hand over their products to large corporations for questionable processing and distribution. Sometimes, they end up tossing out parts that could be consumed.

Image Courtesy of Groco.

Groco chooses to work with cattle ranchers who run mid-sized farms—the ones who are willing to adapt to their way of working. The maximum they work with are five. They say that a small number guarantees farmers earn their fair share, gives consumers time to develop product loyalty, and promotes freshness—“Whatever you find in supermarkets has probably gone through countless distribution centers,” says Pitipong.

Image Courtesy of Groco.

Above all they work together as a team: they teach their farmers the value of nose-to-tail butchery, promote their products, and share profits.

A Seat at the Table

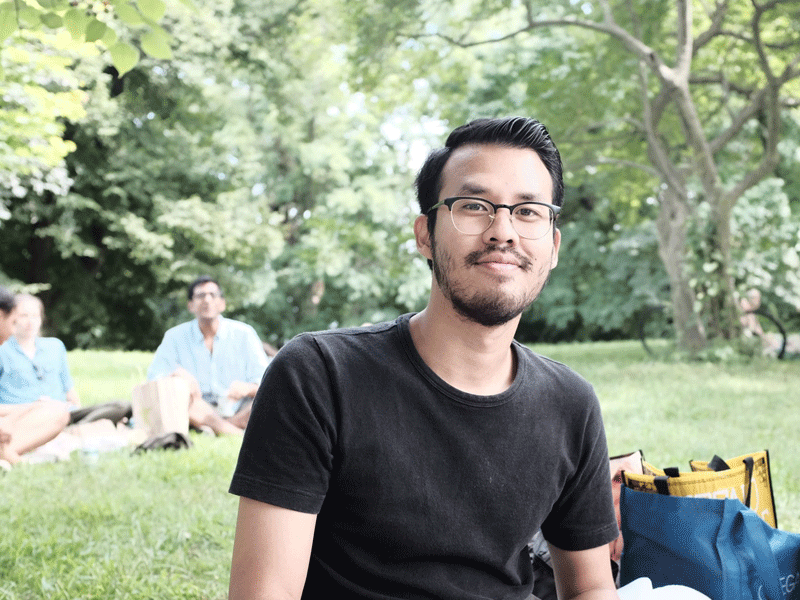

Image Courtesy of Dharath Hoonchamlong.

“When you say words like ‘organic’ or ‘sustainable,’ there is a stigma that leaves people thinking ‘expensive’ or ‘unapproachable,’” Dharath says.

And when large corporations and governments get involved, they further weaken the sustainability of the supply chain, affecting the well-being of farmers, the ecosystem, and consumers.

Small players like Homeland Grocer, Happy Grocers, and Groco could be a catalyst for change in our food system. They open up lines of communication between farmers and consumers. They encourage better agricultural practices. And they give farmers a seat at the table.

“We want to show the farmers and the world that you can do good and make an impact by partnering together,” says Nat. “We are not a charity—it’s a partnership. We are partners.”